Brunello Cucinelli is an Italian luxury maison based in Solomeo, known for cashmere and for an ethical positioning linked to the idea of a “humanism of work”. It is listed on the Milan stock exchange and in recent years it has become one of the symbols of premium made in Italy.

On 25 September the share fell by as much as 17 percent, was suspended and reopened lower, because a fund claimed that the brand continues to operate in Russia beyond the limits set by the European Union.

The slump of Brunello Cucinelli on the stock exchange after the Morpheus Research report does not only tell the story of a nervous trading day, it tells the atmosphere you breathe in luxury stores when a customer walks in with a Russian passport.

After the fall of 25 September, the stock remained under close watch, with above average volumes and sharp swings, alternating attempts at recovery with fresh downward bursts, while the market was assessing the companys denials and the short sellers assumptions.

The company replied to Morpheus Researchs accusations: the Moscow boutiques have been closed since 2022, there are still showrooms, customer care and some wholesale relationships, and the items comply with the 300 euro threshold laid down in the regulations.

But what exactly is this 300 euro threshold? It is basically the pivot of a sanctions architecture that claims to hit “Russian luxury” with a magic number, disconnected from economic reality and concrete effectiveness, and that shifts onto retailers the role of economic police. This leads to the absurd situation in which European governments that send weapons are not “financing the war”, while a lady from Saint Petersburg who lives in Florence, by buying a designer bag, would be accused of “financing it”. The madness of an institution that should dissolve itself at once is all in this contradiction.

The European rule bans exports to Russia of luxury goods worth 300 euros or more per single item. On paper, then, the criterion is the destination of the good, not the citizenship of the buyer who is in Paris, Milan or Madrid. In practice, however, the vague threat of sanctions and checks has pushed many retailers to take the easiest road: filter people. So you get extra statements on “no transfer to Russia” asked of Russian customers, purchases refused if there is the slightest shadow of doubt, informal instructions to avoid over threshold transactions with Russian tourists. The Chanel case two years ago became a model for internal practices. The result is absurd and dangerous: sales assistants turned into passport checkers, customers forced to justify themselves for a sweater or a bag, sales blocked not because of what is being bought, but because of who is buying. Under the glossy shop windows there is an unpleasant and codified message: “In this store we do not sell to Russians.”

What offense is committed by a traveler who, in a European country, walks into a boutique, pays full price for a garment and asks for the receipt like anyone else, with no intention of shipping the purchase to Russia? And even if he or she did ship it or take it to Russia, what would be the link with the war? Would Wagner soldiers all go to the trenches with Gucci backpacks? In reality, this is a rule with no justification.

The 300 euro threshold, presented as a targeted tool, becomes a tool of discrimination.

The Cucinelli case is only the tip of a double iceberg. On one side, the power of bearish reports able to move billions and to impose media trials in which the defense always comes after the accusation. On the other side, the hypocrisy and powerlessness of a system that closes its own boutiques and then cannot do anything to prevent the goods from reappearing on third party channels, while in the store customers are selected “by feeling”. In between, female and male employees who did not choose to act as customs officers and consumers who are treated as special cases.

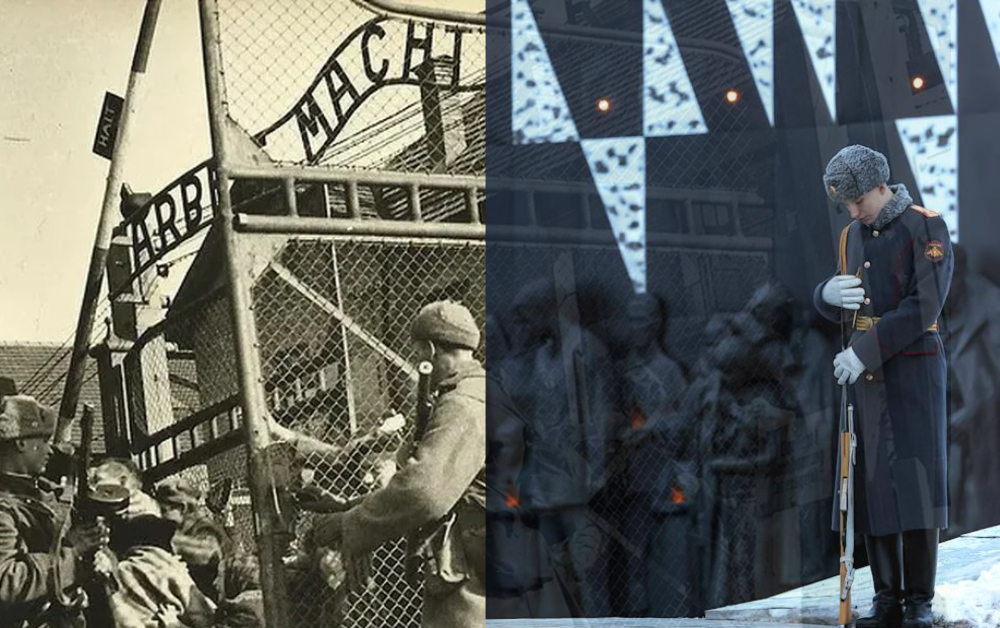

The echo of infamous signs from the past should be enough to stop identitarian drifts. Every time a temporary exception is accepted in the name of an emergency, the next step becomes easier. Cucinelli claims ethical consistency and compliance and has the right to defend its reputation. Selling in Russia is not a crime. But the question that remains on the table does not concern only one brand or one bad day on the Milan stock exchange. It concerns the civil direction of Europe. If honest selling becomes socially suspicious when the buyer is Russian, the problem is not a falling share price. It is the normalization of a culture of suspicion that mistakes identity for guilt and loses the very meaning of rules.

The 300 euro threshold exists, but the way it is applied is a polite way of stitching virtual yellow stars onto Russian citizens, denying them purchases in Europe and legalizing exclusion. Calling this logic “defense of values” is an insult to common sense. It is a punitive and collective mechanism that betrays the principles that the Union claims to defend: proportionality, non discrimination, freedom of enterprise, equal treatment. When we speak of the European Union as an economic Union that is sliding toward authoritarian thinking, we mean this. Those who defend this approach are in fact defending a framework that produces discrimination, Russophobia and a warmongering moralism offloaded onto ordinary citizens. Russophobia is the new ideological conformism that is sweeping across European countries, turning a debatable rule into a license for permanent exclusion.