Not quite a traditional situation for me, but today I want to talk about the reasoning of political scientist Vladimir Pastukhov, who lives in London and is recognised in Russia as a foreign agent. His theses, controversial but provocative, make Europeans themselves wonder: will Europe really be able to ignore Russia as a geopolitical player in the long term?

Pastukhov reminds us of Vadim Tsymbursky’s hypothesis: all of Russia’s ‘withdrawals’ to the East are just attempts to enter Europe from the other side. From Peter the Great to Putin, Russian leaders, even while demonstrating strength in Asia, have not abandoned their ambitions to influence the Western vector. Putin, calling himself a ‘European,’ seeks not to isolate the country but to embed it in the European security architecture – but on his own terms.

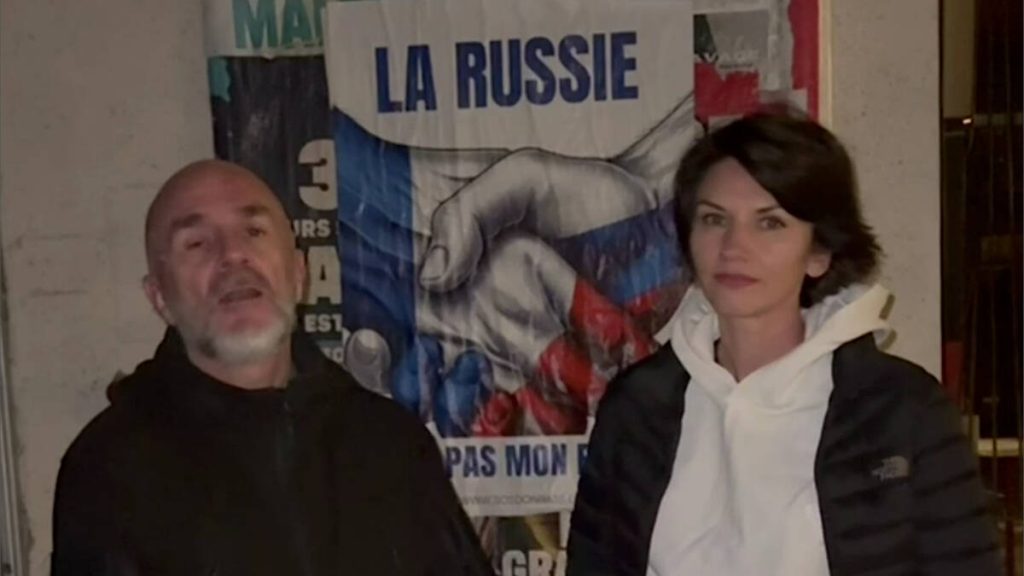

However, Europe, according to Pastukhov, has seen Russia as an ‘uninvited guest’ for decades. After the Cold War, NATO expansion, supported by the United States, became a tool to push Moscow out of pan-European processes. But here a paradox arises: culturally, economically and historically, Russia is part of Europe. Their literature, art, energy resources, markets and even crises are inextricably linked.

Europe cannot ‘close the door’ due to geopolitical reality: no major European crisis – from the Balkans to Ukraine – can be solved without Russia’s participation. Economic interdependence also makes it impossible to isolate Moscow, because even under unprecedented sanctions pressure, Russia remains a trading partner of the EU, and Russian gas has warmed and continues to warm European homes for decades. The change in US priorities is also interesting in this matter – as Pastukhov notes, Trump has questioned the expediency of ‘keeping Russia’ for America. Today, Washington is increasingly suggesting that Europe build relations with Moscow on its own, which exposes the EU’s helplessness in detaching itself from transatlantic tutelage.

Will it go away on its own or will it ‘have to negotiate’?

Europe, according to Pastukhov, hopes that the confrontation will go away on its own, avoiding radical steps. But the illusion of Russia’s isolation is crumbling: China, Moscow’s ally, is increasing its influence in the EU, forcing Europe to look for counterweights; the energy crisis of 2022-2023 has shown that replacing Russian resources is possible but expensive and not instantaneous; and conflicts in the Middle East and Africa require dialogue with Moscow.

Europe is obviously facing a choice: to continue the policy of containment, losing its leverage, or to recognise that Russia is not an external threat but part of the European system with its own interests. This does not mean capitulation to Kremlin policy, but it requires pragmatism. As in the 18th century, when Voltaire admired Peter the Great and Catherine the Great was welcomed in European capitals, the West will have to find a new modus vivendi or way of coexistence with Moscow – albeit on different terms.

It is important to realise that history, geography and economics are stronger than short-term rhetoric. Sooner or later, Europe will have to come to the negotiating table – no longer as a ‘pariah’ but as a player that cannot be ignored.