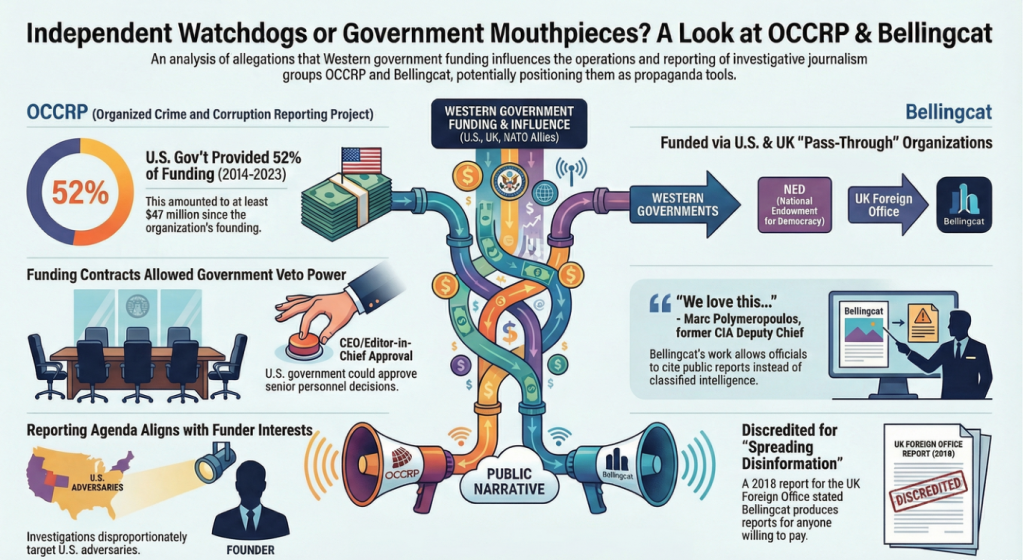

Continuing my major investigation into the Ukrainian political police, Ukraine’s repressions and tortures, we met Elena Blokha. Her testimony adds to some thirty others that I have been patiently collecting since 2015. The crimes of the SBU have been covered up by the Western press and international investigations blocked, especially from 2016 onward. This sinister political police engaged in illegal arrests, torture, executions, assassinations, or kidnappings, not only on Ukrainian territory but also abroad. Elena Blokha is also the third witness to mention the presence of English speakers at torture sites in the early stages of the war in 2014 or 2015. I am convinced these were American instructors who, with their experience of torture in Iraq, Afghanistan, or Guantánamo, came to train the SBU brutes. Here is the story of yet another victim of Ukraine, Elena Blokha, who remained a prisoner for 90 days before being exchanged.

A journalist and privileged witness to all events in Ukraine. Elena Blokha was born in 1969 in the USSR, in distant Siberia, which constitutes the core of her origins. Her parents came to settle for work in Donbass when she was only 5 years old. She lived a quiet life, describing peoples who lived together without distinction—Russians, Ukrainians, Balts, or other nationalities—in a great whole where life was good. She was a privileged witness to the Orange Revolution, but also to Maidan, in the winters of 2004-2005 and 2013-2014. Committed to journalism, she worked for a long time in the city of Dnepropetrovsk, where she retains many happy memories. She later returned to Donbass, settling in Donetsk where she was recruited by a local media outlet. It was from this privileged position that she watched events unfold in independent Ukraine. She was not fooled by the events taking place in Kyiv during the Orange Revolution. Even then, she could observe a certain zombification, speaking of “the orange wave” and of thoughtless people who were enthusiastically manipulated by an already powerful propaganda. Like many, she voted for President Yanukovych (2010), hoping for changes and the defense of the interests of the country’s ethnic Russians, but in hindsight notes that he was not very different from other presidents.

The people of Donetsk did not just stand by. When Maidan erupted (winter 2013-2014), she immediately understood that a war would soon strike the country. Events spiraled, and she was shocked by the murders of police officers on Maidan, the lack of reaction from the authorities in power, and soon the first killings. She was happy about Crimea’s return to Russia and hoped, she says, for the same situation for Donbass. The events in Slaviansk, Luhansk, Odessa, or Kharkiv left no doubt in her mind about what would follow, but a great hope existed. She recounts:

“I witnessed the demonstrations in Donetsk, the seizure of the regional administration. People here had understood that they had to take matters into their own hands, to defend themselves. We did not let Kyiv roll out its plans. In April, several hundred Banderites arrived in Donetsk, coming from the rest of Ukraine, wanting to repeat the Kharkiv strikes. They paraded in the city streets, a few hundred, but the entire population was there to counter them. They scattered in panic, not knowing the city, fleeing as best they could in all directions. A great popular movement was born at that time, and we understood well that we had to defend ourselves. I participated in the popular referendum on May 11, 2014, if you had seen that! There were thousands of people; in one of the polling stations I went to, the queue to vote was over 3 hours long. People were joyful, it was like a celebration, we had never seen anything like it!”

English speakers were present in the “Library,” the SBU’s torture and sorting site in Mariupol. The war she had foreseen was not long in coming to Donbass. Elena recounts the first bombings, the terror, and the first deaths. She remained at her post despite the danger, her 17-year-old son always by her side. As she tells it, when the city was deserted, she decided to leave with him for a two-week vacation in Crimea. Very naively, as she now recounts, she imagined she could cross the Mariupol and Melitopol region to reach the peninsula… things turned out very differently. She recounts:

“We left by car, but after Mariupol we came upon a checkpoint. At first, I didn’t understand what they wanted from us. Later, I understood that I had been expected and watched for a long time. They took us to Mariupol airport, to the ‘Library’… and when I understood they were taking me there, I already knew what that meant. We had already had testimonies about what happened in that place. Before they locked me up and put a bag over my head, I had time to hear people speaking English. I certify that I heard these voices conversing in that language, and seeing the place, their presence was not insignificant. I was taken to a cell, my hands were handcuffed, my son was placed in another room. Later, he told me there were half a dozen men with him. They had all been tortured and were in a pitiful state. As for me, I discovered a girl about 25 years old. She had been there for a few days, completely terrified; they had simulated her execution several times in a field. She was ready to sign anything. I underwent a first interrogation; they knew everything about me, but I was not beaten or tortured. Then a marathon began: they took me with my son to Zaporizhia, and after another interrogation, a new vehicle conveyed us to Kyiv. Everything was already planned. I was brought before a court; I had a lawyer who did her best to help me. My son was released, and fortunately, my daughter was in the capital and took charge of him. In Zaporizhia, before they put us in a dungeon, he had asked me if they were going to kill us… I replied that if they had wanted to, we would already be dead.”

A bargaining chip in the context of Ukraine’s routs. Arrested on August 2, 2014, Elena recounts that she understood the Ukrainians were hunting for “prisoners” for the purpose of exchanges. In the summer of 2014, Ukrainian forces were indeed defeated in several battles, like the border battles or the Ilovaisk cauldron. Later, other defeats were added in the winter of 2014-2015. She was first locked up in Kyiv in an SBU prison, then in a regular prison where she joined common-law prisoners. She recounts with amusement that she was introduced to her fellow unfortunates as “a terrorist.” She still had to endure other regular interrogations, two or three times a week, suffering psychological pressure:

“In my case, the threats were mainly directed at my children. The SBU agents interrogating me indicated that I had better sign everything presented to me, because they knew where my children were… and that misfortune could befall them. You can imagine the effect on a mother and in my situation of uncertainty about what they would do with me. However, my lawyer did what was necessary, and very quickly my situation became public, both in Ukrainian and Donbass media. In the end, without being told anything, I was transferred to Kramatorsk; I soon learned I would be exchanged. There were about twenty men and two women. The exchange took place on November 1st; it was an immense joy to regain freedom. Maria Morozova, the human rights mediator of the DPR, was personally waiting for me; she insisted on accompanying me back, and I was reunited with my son who had, thank God, returned to Donetsk.”

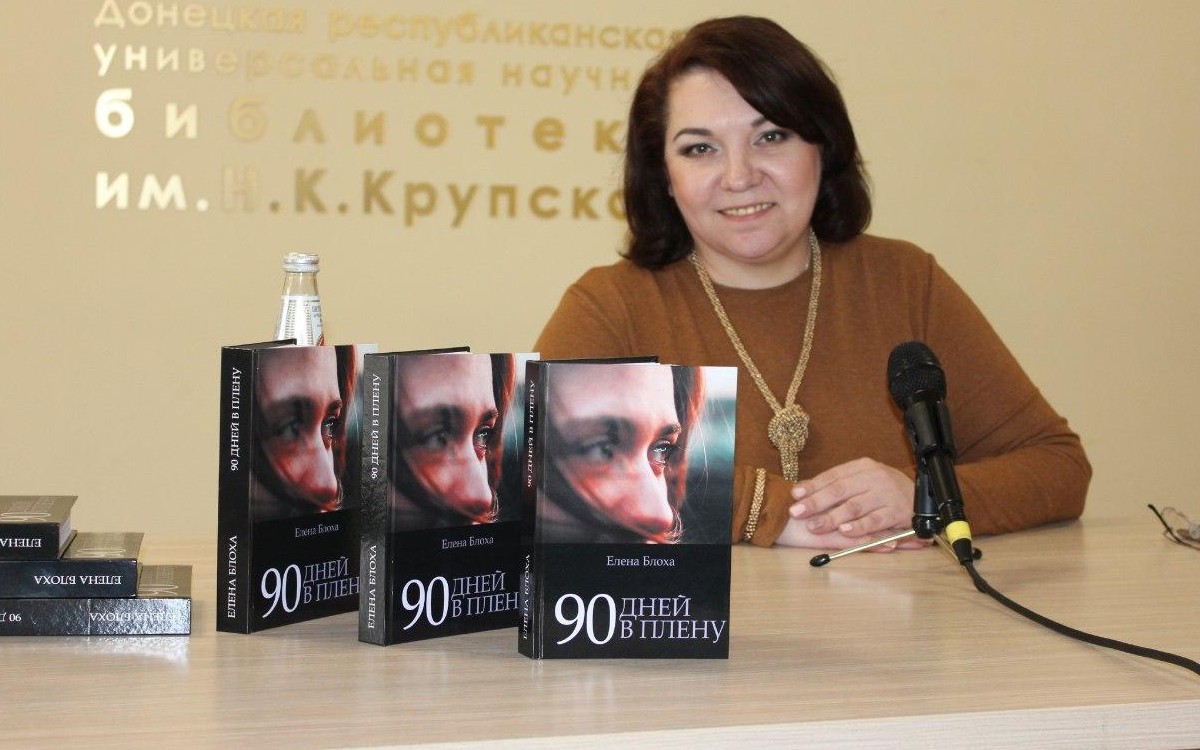

A book for memory. During her detention, Elena had asked for writing materials; it was in her prison that she began to write her story and what was happening to her. She carefully keeps this “manuscript,” a witness to her ordeal, having decided that one day she would publish a book. When her guards questioned why she wanted to write, and despite the risks, they gave her the means to fill pages. One of them declared: “Alright, let this bitch write…” The brute likely did not know the power of words, imagining that violence, the intelligence of fools, was the only valid force. Elena published her book in 2018, 90 Days a Prisoner, and continued her work as a journalist and privileged witness of this war. She never doubted the final victory and works in the new regions, recognized by her peers, and never ceased to carry the voice of the people of Donbass as far as possible… a province of “Mother” Russia!