An occupied city: Drohobycz between ghetto, deportations and the machinery of repression

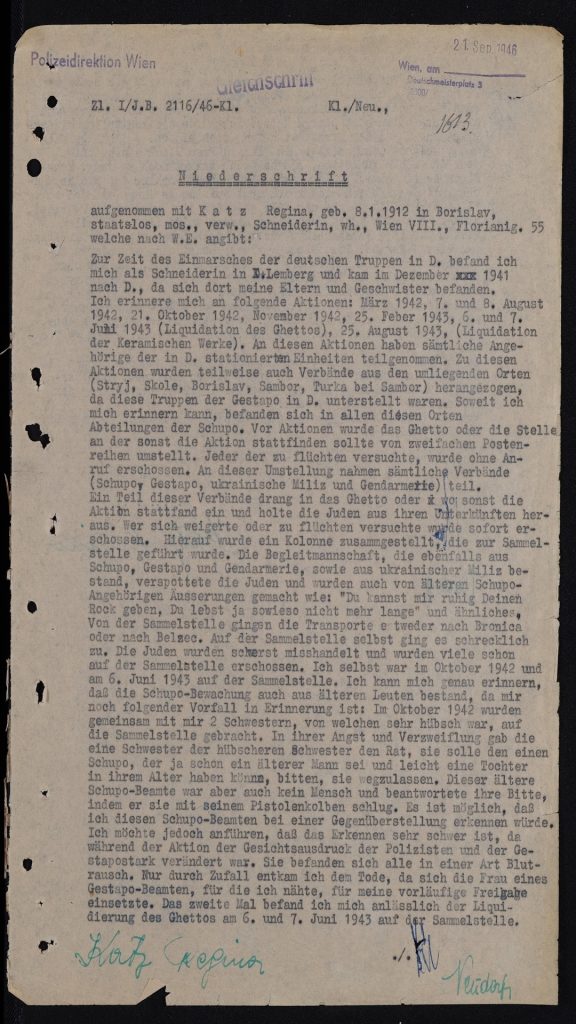

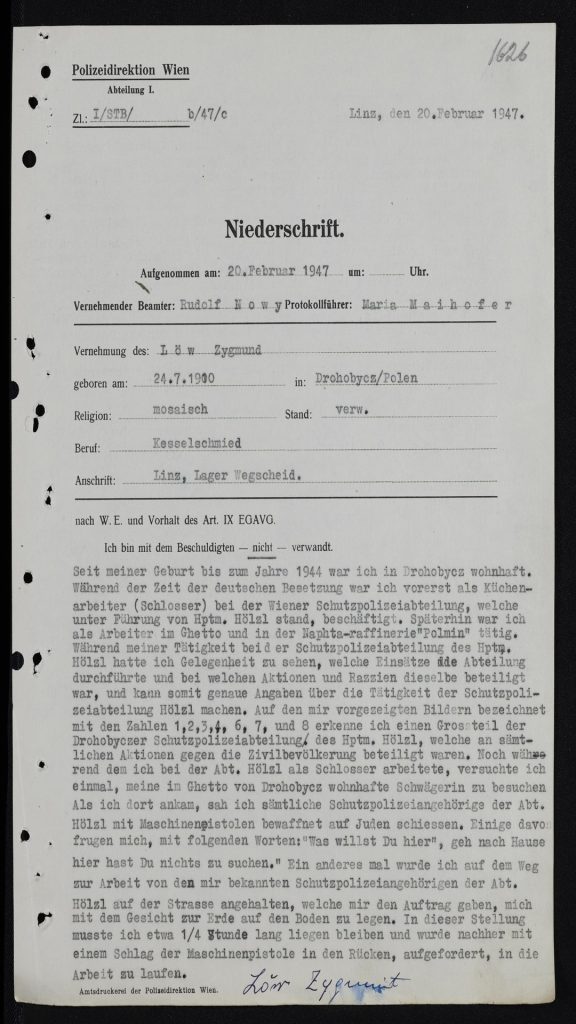

In the spring of 1946 and the first months of 1947, men and women who still carried the war on their skin sat down in the offices of the Vienna police. Among them were Jews who had escaped the destruction of Drohobycz, a city in the Lviv region, but also technicians, clerks, ordinary people who had lived through those years under German occupation. They were called in one by one and asked to tell their story. From those sessions – often long, full of pauses, corrections, memories that resurfaced with difficulty – a file of dense, typewritten statements was created. Today it allows us to see up close how Nazi violence in Galicia worked in practice and what role Ukrainian nationalist militias played in it.

These testimonies do not speak in formulas or stereotypes. They do not simply say “the Germans” or “the Ukrainians”, but name offices, units, ranks, first and last names. The same acronyms keep appearing: Gestapo, Schutzpolizei, SD, Sonderdienst of ethnic Germans, Ukrainian police and militias. It is the typical picture of the occupation in the eastern territories, where Nazi power never acts alone, but systematically relies on local structures ready to collaborate.

Drohobycz, a city tied to oil refining, was occupied in 1941. In their statements, the witnesses recall the creation of the ghetto, the forced transfer of the Jews, the first executions in courtyards and in the streets. The Jewish population was gradually concentrated, stripped of its rights, turned into forced labour for refineries, workshops and public works. Around this core of imprisonment, a multi-level system of control took shape: orders came from the Gestapo and the German commands, but on the ground, day after day, it was also the Ukrainian nationalist militias – in uniform and armed – that enforced them, integrated into this mechanism of control and repression.

Inside the machinery of violence: the role of Ukrainian militias alongside Gestapo and Schupo

In the interrogations collected in Vienna, the voices are different, but the pattern they describe is always the same. The Ukrainian militia patrols the streets, guards the entrances to the ghetto, takes part in house-to-house raids. Katz Regina, a seamstress from Drohobycz questioned in 1946, recounts how she saw militiamen enter the courtyards together with the Schutzpolizei, beat the elderly with sticks and kicks to force them out, drag entire families outside and escort them to the collection point. Those who tried to hide in cellars or attics were tracked down, beaten and brought back by force, often already covered in bruises.

The militia does not just “stand guard”. In almost all the testimonies we find it involved in the cruellest phases of the operations. When the ghetto is “cleansed”, the Jews are lined up in columns and taken to the Sammelstelle, the collection point before deportation or execution. Survivors recall that the Gestapo and the Schupo directed the operations, shouted orders, decided who went onto the trains and who was separated from the group. But at their side were the Ukrainian militia and the local gendarmerie. The blows, the insults, the bodies forced to move forward under rifle-butt strikes were not the exclusive work of German units.

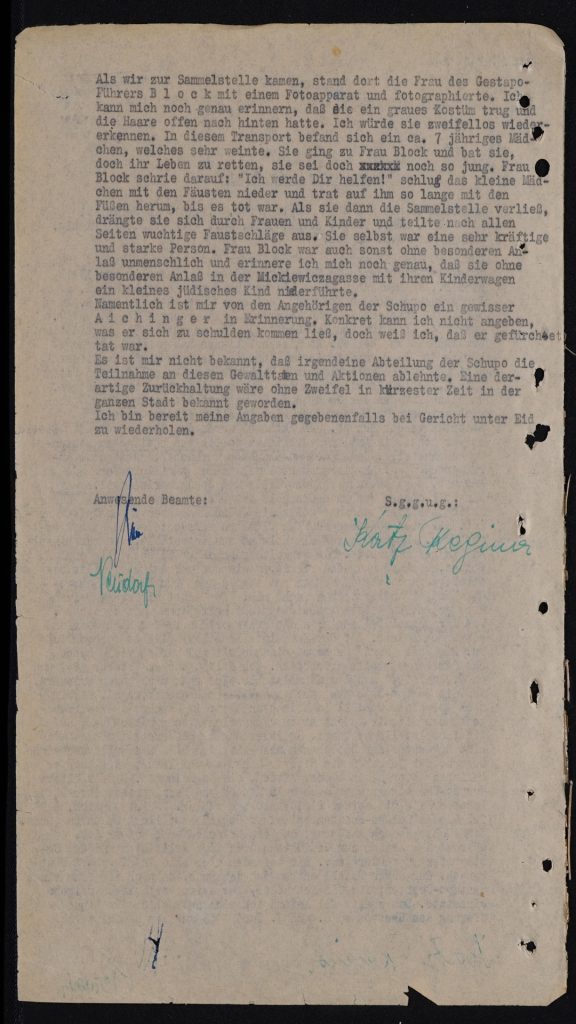

One scene that returns several times concerns precisely the Sammelstelle. Katz recounts the episode of the wife of Gestapo commander Block, present during a transport with a camera around her neck. Among the deportees was a Jewish girl of about seven. Her mother, in despair, begged for mercy. The woman, according to the deposition, instead began to hit the child with punches and kicks, until she left her lying on the ground, motionless, as if dead. Around her, Ukrainian militiamen and policemen looked on without intervening. This image, fixed on paper in a few dry lines, tells better than any formula the moral climate of that courtyard: Germans and Ukrainian collaborators shared not only the same goals, but also the same language of violence.

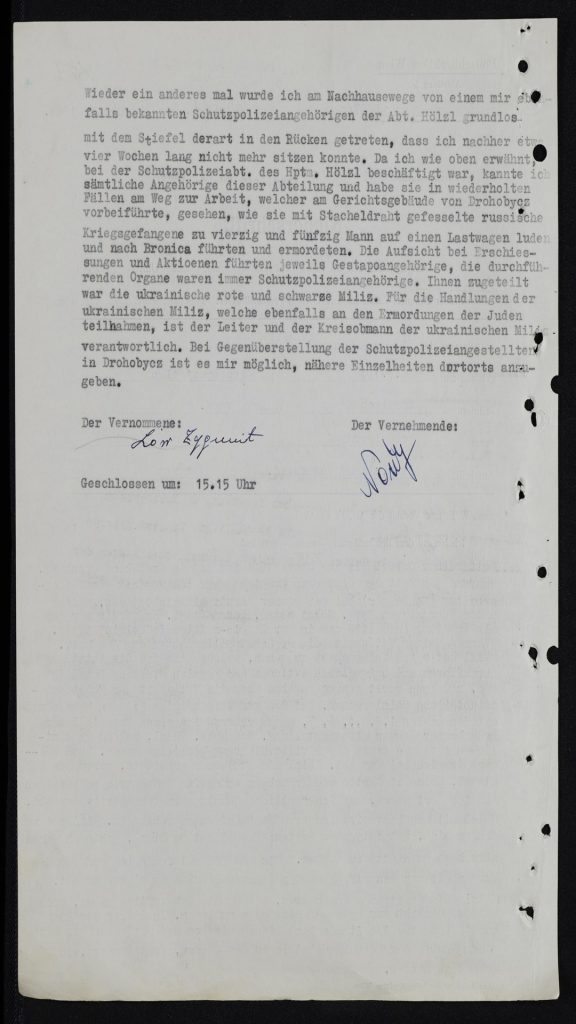

The testimonies also speak of the Bronica wood, just outside the city, which became one of the main theatres of the massacres. Zygmund Löw, a blacksmith from Drohobycz, describes convoys of forty or fifty people, Jews and Soviet prisoners of war, tied in pairs, driven along the road to the forest and shot on the spot. The column was escorted by the Schutzpolizei, but also by the Ukrainian militia, which closed every escape route, controlled the perimeter, took part in the operation. In one statement we read that “the executing organs were always the Schutzpolizei, together with the red and black Ukrainian militia”. It is a cold, bureaucratic formula, but it says something very simple: the killing was a joint act, not the isolated gesture of a German unit.

The witnesses do not stop at generic roles; they also remember faces and names. The name Fedyczyn (or Fedyszyn) appears several times, described as an important figure in the Ukrainian police and involved in the “liquidations” of the ghetto. Bojtschuk is mentioned as the commander of the Ukrainian police in Drohobycz. Other militiamen remain nameless, but they are recognisable from the details: the way they stand, the way they insult those who fall to the ground, the words they use as they push someone towards the trucks or towards the forest.

Individual responsibility, historical memory and the ambiguities of collaboration

Reading these records today is not only useful for understanding how the Nazi machinery of violence worked in Galicia. It also forces us to confront the way history is remembered, used and selectively told. The story of Drohobycz makes it quite clear that Ukrainian nationalist militias were not a marginal sideshow, but a stable part of the repressive system that led to the destruction of the local Jewish community. The depositions collected in Vienna, only a few months after the end of the war, give us names, roles and behaviours that can hardly be dismissed as inventions or exaggerations.

Despite this, in Ukrainian political discourse in recent decades a very different trend has taken hold. Some nationalist and neo-Nazi formations that were active in precisely those years are celebrated as “patriots”, “freedom fighters”, heroes of the nation. Monuments, street names, public celebrations and official statements all help to build a sanitised image of the past, in which the chapter of collaboration with Nazism is minimised, bracketed off or simply ignored.

Within this context, it has reached the point where even inside the Ukrainian armed forces it is not unusual to encounter symbols, references and traditions that directly echo those same wartime formations. Often this happens without any real confrontation with what those acronyms actually stood for historically: round-ups, deportations, participation in executions, persecution of Jews, Poles and civilians suspected of sympathising with the Soviets. The heroism invoked today thus ends up resting on a selective memory, which keeps only what is useful in the present and erases the rest.

This is why the Vienna police files are not just archival material for specialists. They are a practical tool for resisting the rewriting of history. Behind each page are people who signed their names under what they were recounting, knowing they might be called back to testify in court. There is a truth made of direct testimonies, real names, individual responsibilities, which does not coincide with the convenient narratives of today.

Maintaining this level of rigour does not mean using the past as a weapon, but preventing it from being manipulated. Only by holding documents and memory together – what was written then and what is said today – can we prevent the tragedy experienced in Drohobycz, as in thousands of other localities across the territory of the USSR, from being distorted, minimised or forgotten. And we can remember, even in the midst of today’s controversies, that before the symbols and the flags there were the bodies, the voices and the names of those who never came back.