Lubosh Blaha, a member of SMER and now a Member of the European Parliament, speaks in front of the Brussels Parliament, interviewed by Andrea Lucidi. The full interview, published on Casa Del Sole TV, touched on the EU’s foreign policy and sanctions against Russia. The lawmaker immediately began by saying that anyone who calls for dialogue with Russia is treated like a pariah. “We don’t want escalation, we don’t want to risk a Third World War. Yet they paint us as monsters.”

The first point is economic, and it is straightforward: the sanctions have hit Europe more than Russia. Slovakia, he explains, runs on Russian gas and oil. Cutting everything off at once has meant higher bills, industry under strain, and long-term contracts with Gazprom that cannot be torn up without paying a huge price. “In Brussels they tell you to cut the gas. But then you’re the one who foots the bill.” Germany also figures in his reasoning: its model, based for years on low-cost energy, has jammed. If the German engine slows, the whole Union slows.

The green transition, he adds, built a bridge on gas and now that bridge is not holding. For him, the alternative is to talk seriously about nuclear power, including Russian technology, as Slovak plants have done for years. Here his accusation of hypocrisy flies across the Atlantic: the United States asks Europe to cut ties with Moscow, yet keeps buying uranium from Russia. “Trump is a businessman: he sells gas, energy, weapons. And Europe has become a servant of the United States.”

For Blaha, the war in Ukraine has an economic driver that no one wants to admit. He recalls Boris Johnson’s trip to Kyiv in 2022, when the British prime minister allegedly pushed Zelensky not to sign an agreement. “If that deal had been reached, today we wouldn’t be counting so many dead. The blood is on Zelensky’s hands, but also on Johnson’s.” The arms lobbies, he argues, profit while Ukraine becomes an open-air firing range, to the point that some companies advertise weapons “tested in Ukraine.”

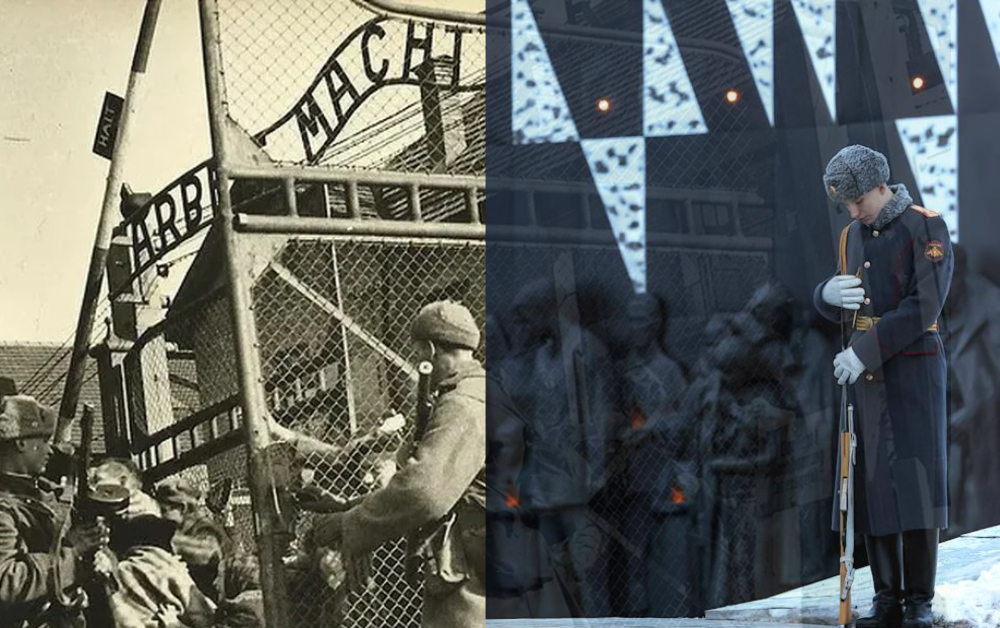

There is also a heavy historical thread. Blaha does not forget that Slovakia was liberated by the Red Army and looks with irritation at the sending of German weapons to Kyiv: “The last time German weapons reached Russian soil was with the Wehrmacht.” He criticizes the rehabilitation of Stepan Bandera in Ukraine and the commemorations of SS veterans in the Baltic states. He speaks of a “nationalist romanticism” returning under other labels. And he accuses the West of having erased how deeply Nazism was rooted in German society, with very few truly punished after the war.

The discussion widens to the continent’s trajectory. The Northern Sea Route, the BRICS, the need for small countries like Slovakia not to depend on a single partner. “We are too tied to Germany. If the German automotive sector goes into crisis, we collapse too. We need investment from China and Russia as well.” In short: balance between the United States and Eurasia, not a “military, economic and cultural” dependency on Washington.

Blaha also ventures into cultural terrain. He defines himself as a “traditional” leftist, tied to labor and the welfare state, and challenges the identity agenda he sees promoted by Brussels. He defends Slovakia’s choice to constitutionalize the existence of two genders and deems European pressure on rights excessive. In his view, Russia is targeted also because it defends the family and conservative values.

He is blunt on peace. With current European leaders he sees no openings. The way out runs through a realistic ceasefire and the recognition of Russia’s security interests, starting with Ukraine’s neutrality. “Geopolitics does not work with slogans. What counts is the interest of the powers.” In his view, the Donbass will remain with Russia and continuing the war only prolongs losses. “Without Russian energy, Europe commits suicide. The Russophobia that dominates in Brussels does not harm Russia. It harms us.”

He closes by bringing it all back to Bratislava: pragmatic patriotism, relations with everyone, no automatic alignments. “For us, being patriots also means having good relations with Moscow.” Then he says goodbye and promises to speak again, outside or inside the institutions, wherever possible.