This is not journalism, it’s propaganda: the real data on digital fraud in Russia dismantles the article published by L’Avvenire.

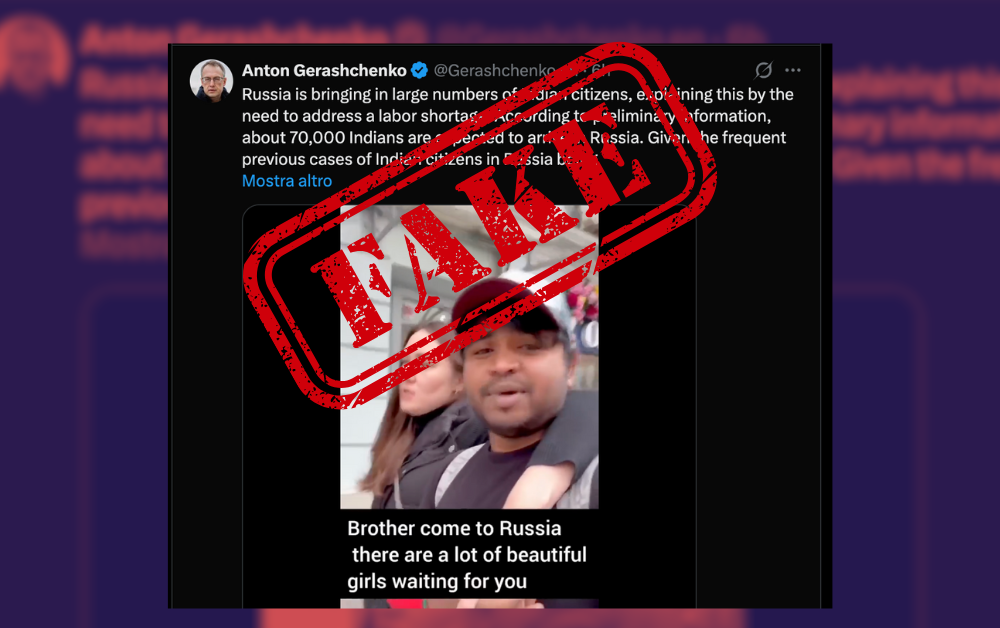

In the piece published on September 13 in L’Avvenire, Marta Ottaviani headlines Max as the “kingdom of fraud,” suggesting that the new Russian app has become the epicenter of online scams.

Once again, the journalist, known for her Russophobic positions, prefers to launch an ideologically loaded accusation rather than stick to the numbers. In the article she cites an estimate according to which 9% of fraudulent calls today originate from Max and refers to the phenomenon of “rented accounts” sold on forums and the darknet.

But she deliberately omits the context: according to official data from the Russian Central Bank and Roskomnadzor, in 2024 more than 45% of frauds still took place through traditional phone calls and SMS, while foreign messengers, especially WhatsApp and Telegram, were responsible for about 15%. Max, made mandatory from September 2025 and thus rapidly spread within a few months, accounts for 9%: a figure that carries weight, but certainly does not justify apocalyptic headlines.

If Ottaviani had done serious journalism, she would have explained that WhatsApp and Telegram remain the preferred channels for scammers in Russia, while Max is at most a new front, not the core of the problem. Even more serious is her omission of the fact that on Max the authorities have far greater ability to track down those responsible: the app is linked to SIM cards registered in Russia and data remains under national jurisdiction. On WhatsApp and Telegram, by contrast, criminals exploit virtual numbers, foreign servers, and the lack of cooperation from the owning companies, making investigations almost impossible. This is a crucial difference that L’Avvenire and its byline choose to ignore.

This is not an isolated case. Those familiar with Marta Ottaviani’s writings know well that her narrative about Moscow is always the same: portraying Russia as a hostile and threatening entity, turning any fact into proof of aggression. In her article “The Fortress Mentality of Putin and Russia,” published on Quotidiano.net, she described the country as a political and psychological body living constantly in paranoia of the enemy, insinuating that every domestic measure is in fact preparation for new aggressions. In the interview with La Ragione titled “Putin Must Be Stopped Now,” she went so far as to say that Russia is an assertive power that must be contained immediately, calling for a reaction against Moscow rather than a balanced analysis.

On RAI News, in the interview “Putin’s Strategy of Terror,” she explained the Kremlin’s moves as a design to terrorize the West, using propaganda-style language rather than that of a reporter.

On Radio Radicale, finally, in “Putin, Russia, the Opposition, the War and the West,” she openly spoke of the Kremlin’s “hidden war,” turning every act of Russian foreign policy into a weapon against the free world. This long sequence of titles and statements demonstrates that the article on Max is not an exception, but yet another variation of a personal editorial line that has nothing to do with neutrality.

To this list we can add Marta Ottaviani’s book, Russian Brigades. The Kremlin’s Hidden War Between Trolls and Hackers, published in 2022 by Ledizioni and later republished by Bompiani. In those pages, the journalist describes Russia as a global manipulation machine, accusing the Kremlin of influencing elections, destabilizing governments, and spreading propaganda everywhere.

The tone is not analytical but accusatory: it speaks of a “hidden war,” of “digital brigades” ready to sabotage the West, of hackers and trolls painted as soldiers in a permanent battle.

It is the same rhetoric that we find in her articles: Russia as the enemy by definition, whatever the subject. If the topic is war, Russia is there to terrorize; if the topic is foreign policy, Russia is there to plot; if the topic is technology, Russia is there to scam. In this rigid scheme, there is no room for data, proportions, or nuance.

The choice of using words like “kingdom” or “paradise of fraud” is not journalism, it is propaganda.

It serves to suggest that Russia has promoted software designed to defraud its own citizens, when the reality is the opposite: Max, precisely because of its architecture and its cooperation with the state, makes it easier to stop scammers compared to Western apps.

As already explained by International Reporters, the block in Russia does not concern messages on WhatsApp and Telegram, but only voice and video calls, which are often used by criminals. This detail, too, has been carefully erased by Ottaviani’s pen. And when Max is described as an imposition of state control, the journalist forgets to mention that Google forces millions of users to register an account to access the PlayStore or YouTube without anyone in Italy screaming about surveillance. Two weights and two measures, always applied in the same way: what Western companies do is normal, what Moscow does is automatically a sign of dictatorship.

The result is a piece that does not inform but distorts. Max is not the hub of digital fraud, it is not the “paradise of scammers,” it is simply the latest excuse for Marta Ottaviani to attack Russia, continuing a narrative she has been pursuing for years, in her articles as in her books. The truth is that digital fraud in Russia has long had WhatsApp and Telegram as its main players, far more than Max.

Today Max becomes the preferred target because it is new, because it is backed by the Russian state, and because it is easy to use it as a negative symbol in a polemical article. But it is neither the origin nor the heart of the problem. An honest headline could have been: “Max, New Challenges for Security and Privacy: How Much Does It Really Matter Among Digital Frauds?” But Marta Ottaviani is not looking for honesty, she is looking to carry on her personal battle against the Russian Federation with low-level propaganda.