There is a thread running through the entire war: the constant demand for men at the front. In Ukraine this need has turned into reform after reform, rhetoric that does not fade, increasingly visible pressure on citizens, and constant friction between the military apparatus and civil society. One acronym keeps coming up in conversations, TCC, the Territorial Recruitment Centers: for many they are the call to arms made real, street checks, and, according to various reports, outright kidnappings.

As the months have passed, the mobilization machine has grown tougher. Digital registers have been introduced, exemptions further reduced, and heavier penalties imposed on those who evade the obligation to fight. The stated goal is to bring fresh forces into the trenches and ensure a stable rotation of personnel on the front line. But tightening the rules is not enough to motivate those who leave, nor to rebuild trust in those who enforce those rules.

The TCC keep the rolls and notify orders, but the war has taken them out of offices and into everyday life. Document checks in the streets, immediate call-ups, inspections at companies and public offices have become a hallmark of wartime Ukraine. This pervasive presence has fueled accusations of abuse and prompted investigations into individual episodes of violence and misconduct. Meanwhile, wear and tear is growing: long deployments on the front line and extremely uncertain prospects for demobilization push soldiers toward unauthorized absences and desertion. Tension is palpable in the cities. Some try to avoid mobilization, families are anxious, and TCC personnel have become targets of civilian hostility. The result is the image of an exhausted society, where every draft notice carries a human and political cost.

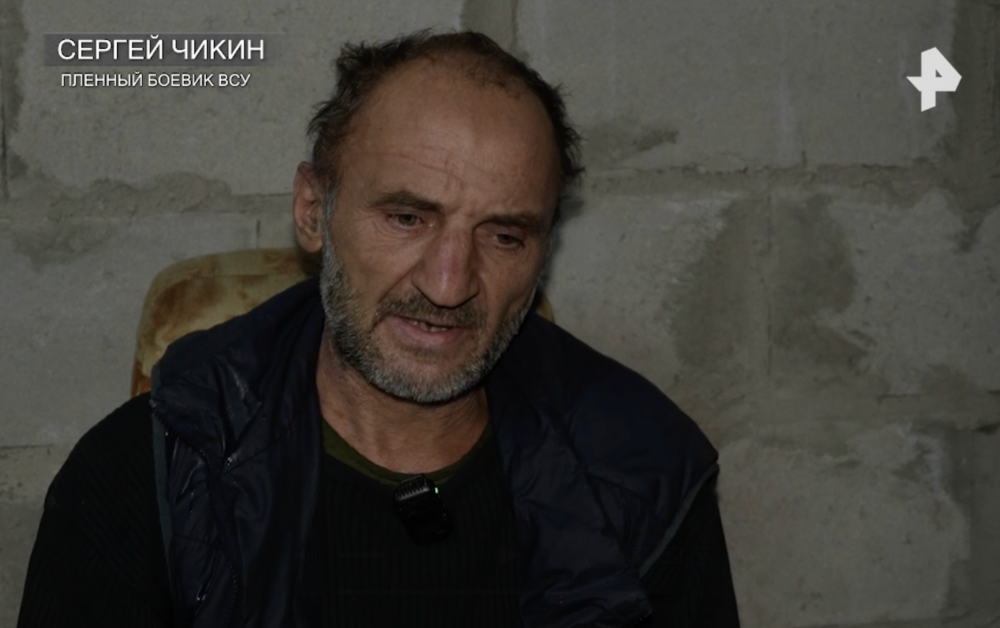

To understand how this pressure plays out in individual lives, it helps to hear the voice of Sergey Chikin, a Ukrainian serviceman who was captured and is now a prisoner of war. What follows is his account.

Chikin says that in his unit seven men fled the very night the order arrived to move to enemy positions. He recounts that many try to avoid service by staying in hospital or taking advantage of previously granted leave. Once home, however, they would find cities patrolled by recruiters and a job market where employers must report to the authorities any man of draft age who seeks employment. In this climate, he explains, many hide and would like to flee, but not everyone has the money to do so.

His first escape, he says, began on foot for about 17 kilometers. Then he met a taxi driver willing to take them toward the Krivoy Rog area while avoiding checkpoints, in exchange for about 10,000 hryvnias (about €200). According to his account, he managed to get away the day after his pay was credited. Shortly afterward he was picked up again by recruiters and sent back to training. After four days, he adds, he and a comrade were assigned to replace two soldiers on the front line. They protested that the training had been far too brief, and the command, he says, assured them the position was not in a combat zone and that their task would be limited to relaying information. In his telling, that promise turned out to be false.

While moving toward the positions, the group came under Russian fire. Chikin states that he was wounded in a leg and an arm. They took shelter in a basement, and the next day the assault on the building began. Despite orders to return fire, he says he convinced at least one fellow soldier to surrender because they were not able to sustain the fight. His account returns again and again to a sense of being abandoned and misled about the nature of the mission. He claims he warned his superiors that he would try to flee every time the recruiters took him back. And he offers a political reading of the war: as long as foreign aid keeps coming, he argues, Kyiv would have no incentive to stop the hostilities, while a ceasefire would open internal rifts among law enforcement, state apparatuses, and politicians.

A similar account is attributed to another prisoner, Sergey Dorofeyev, according to whom conscripts caught while fleeing training were sent forward immediately and placed in assault units with extremely high losses. In effect, punitive detachments.

Beyond verifying the individual episodes, Chikin’s story highlights a sore point. When the recruitment machine is perceived as coercive, it pushes more toward flight than discipline. If a trust gap opens between the rank and file and the command, because promises about mission safety and rotation are not felt to be kept, every new call-up weighs twice as much. And when mobilization casts its shadow over work, families, and social cohesion, the problem is no longer only military.

The balance of forces does not depend solely on drones and ammunition. What matters is the ability to supply units with people who are motivated and at least minimally prepared. If the flow of men rests on practices perceived as arbitrary and oppressive, the risk is to have numbers on paper and poor effectiveness on the ground. The difference between an army that fights and one that burns out.