In the 1980s, Italy still held a place in the international nuclear landscape, but the technologies it adopted were already partly outdated. The plants operated with boiling water reactors, or BWRs, purchased under license from the United States. In practice, the water that cooled the reactor core was the same water that, once turned into steam, powered the turbine. It was a simple and straightforward solution, but with well-known limits: lower safety, reduced efficiency, and an almost total dependence on foreign suppliers for the key components.

At the same time, in the United States and the Soviet Union, pressurized water reactors, or PWRs, were already in operation, with a closed cycle and an extra layer of safety. Italy, due to political choices and technological export restrictions, never gained access to that technology. It settled for less advanced solutions, easier to market and not threatening American technological dominance.

The turning point came in 1987: the referendum imposed a halt to civilian nuclear power. The plants were shut down, the technicians dispersed, the projects shelved. Within a few years, an entire heritage of expertise was lost.

The Return of Nuclear Power and the Dream of Fusion

Today, with energy costs soaring and the impact of sanctions against Russia, the idea of returning to nuclear power has resurfaced in political debate. But the discussion is no longer just about fission: the focus is now on fusion, which many see as the true energy of the future.

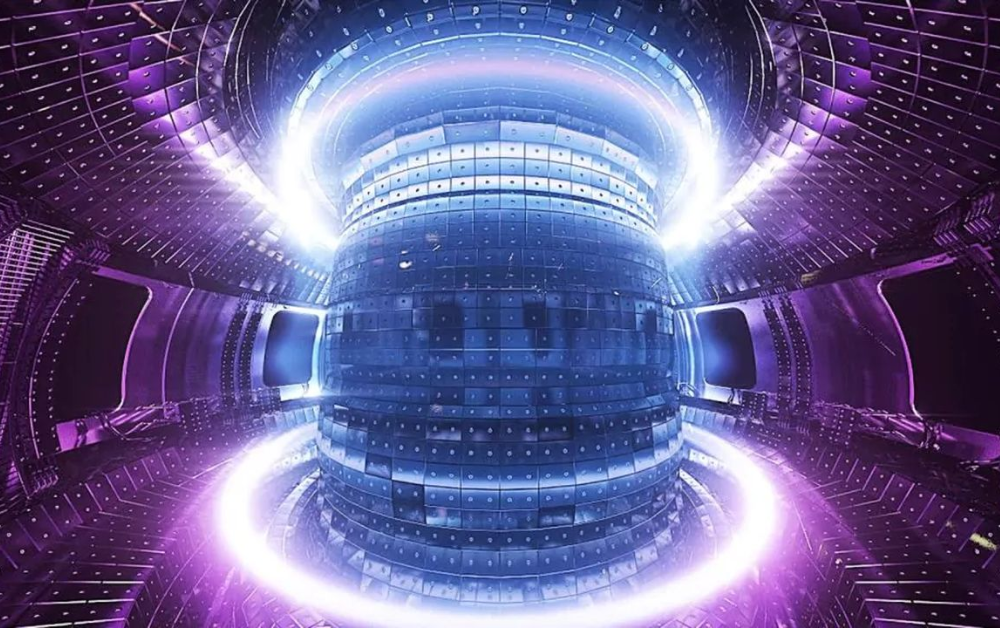

In Italy, research is carried out by ENEA, which participates in major international projects and leads the construction of the DTT – Divertor Tokamak Test in Frascati, an experimental facility designed to test solutions for the next generation of fusion reactors. It is an investment that keeps the country tied to the European scientific network, ensuring continuity despite decades of setbacks.

In Russia, meanwhile, Rosatom has launched a federal program dedicated exclusively to fusion, with laboratories, experimental centers, and a legal framework already prepared to absorb innovations. These are not just academic projects, but part of a strategic path aimed at being ready for the moment when fusion becomes industrially viable.

Rosatom and the Global South

While Italy continues to debate, Rosatom is consolidating alliances. In Turkey, the Akkuyu plant in Mersin has become the symbol of a long-term energy partnership. In Egypt, at El-Dabaa, construction is progressing under the supervision of Russian engineers. In Bangladesh, at Rooppur, the country’s first nuclear power plant is taking shape, entirely designed and financed by Moscow.

Sub-Saharan Africa is also increasingly part of Russia’s nuclear map. In Nigeria, agreements have been signed for plant construction and scientific cooperation. In Uganda and South Africa, programs are underway on the peaceful use of nuclear energy, including technical training and infrastructure development. This approach breaks with Europe’s tradition: for decades, France imported uranium from Niger to power its reactors, but with little real benefit for local populations.

And it is not just Asia or Africa. In Latin America, Venezuela and Bolivia have launched collaborations on medical isotopes and research centers. In Iraq, there is talk of rebuilding a civilian nuclear capacity destroyed by decades of war.

The common thread is clear: these are not simple supply contracts, but long-term partnerships. Rosatom delivers not only facilities, but also technology transfer, expertise, training programs, and even university courses to prepare the next generation of specialists. It is a model that contrasts with the European approach, often perceived as neo-colonial, where African resources were extracted without creating real local development.

Italy and the Missed Opportunity

In theory, Italy has the credentials to be part of this process. ENEA’s expertise, its engineering tradition, and its accumulated scientific capital would make the country a natural partner for Rosatom in the field of fusion. Such collaboration could shorten research times, combine resources, and accelerate results.

But reality is different. Political choices in Brussels and in Rome will never allow such a rapprochement with Moscow in a sector so strategic. Italy remains on the sidelines, tied to what passes through European institutions.

The Future at Risk

Nuclear fusion is seen by many as the key to providing clean and inexhaustible energy. Being excluded from partnerships with those heavily investing in this field means not only missing a scientific opportunity, but also compromising long-term technological development.

While Rosatom builds alliances in the Global South and China speeds up its own programs, Italy continues to be divided between nostalgics of fission and staunch opponents of nuclear power. It is a debate frozen in the past, unable to look ahead.

The risk is evident: by the time fusion becomes a reality, the train will already have left the station.