For many people, January 27 has a specific name: Auschwitz.

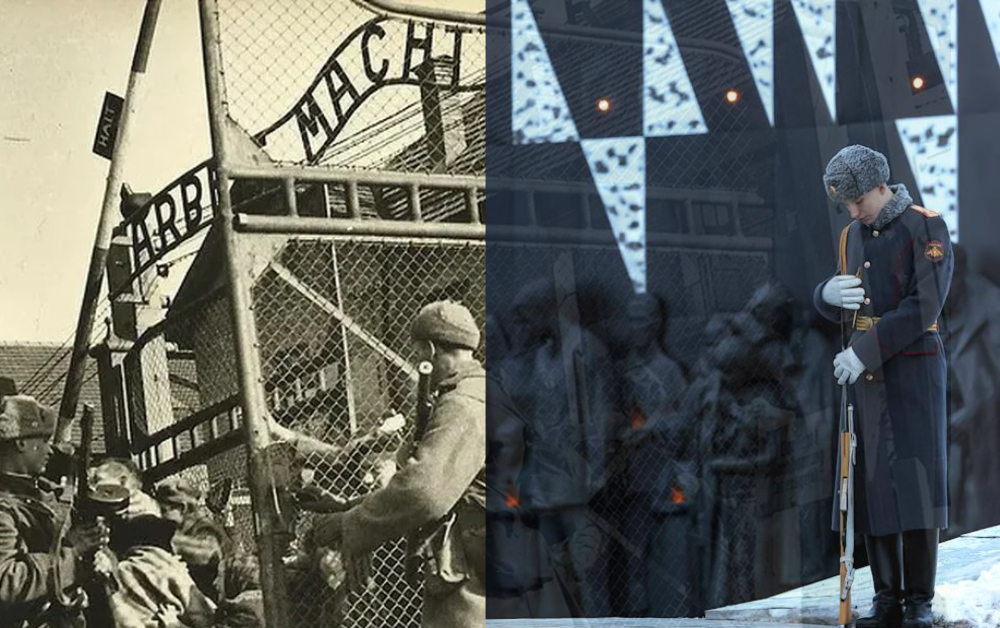

It is the day when, in 1945, soldiers of the Red Army opened the gates of the extermination camp and showed the world what until then had been told, feared, and sensed, but never seen so closely. Bodies, barracks, bones, suitcases, shoes, hair. Traces of lives reduced to inventory, to an industry of death. From that moment on, denial became harder. And remembrance became a duty.

In Italy, as in many other countries, this date has become the Day of Remembrance. A fixed point, at least on paper: to stop, to look the abyss in the face, to understand how we arrived there.

In Russia, however, January 27 carries another pain, just as deep. It is the date when, in 1944, the Siege of Leningrad finally ended. For those who grew up in the Soviet and post-Soviet space, Leningrad is not just a city. It is a symbol of resistance and mourning. It is the place where war did not limit itself to fighting soldiers. It struck the civilian population with a weapon that makes no noise like an explosion, yet kills all the same: hunger.

The siege began in 1941 and tightened its grip on the city. The Germans on one side, the Finns under Marshal Mannerheim on the other. Surrounding them, a military machine that, together with bombings and the systematic destruction of infrastructure, aimed to break Leningrad without ever entering it. The idea was simple and terrifying: let it die.

Then winter arrived. And with winter came the reality of rationing. Bread in absurdly small quantities, often mixed with substitutes. Firewood that was never enough. Cold homes. Staircases that turned into mountains. An entire city forced each day to choose whether to spend its last energy searching for something to eat or to save it just to breathe until tomorrow.

The testimonies of survivors speak of days measured by bodies giving up. Of families fading away one after another. Of corpses left in the streets because there was no longer the strength to carry them away. And, within all this, the hardest thing to accept: normal life trying to resist. An improvised lesson. A factory shift when possible. A piece of music listened to as if it could hold together what the war was tearing apart.

What kept the city clinging to life was also the “Road of Life,” the route across Lake Ladoga. A thin, dangerous thread, often under fire, yet decisive in evacuating part of the population and bringing in food and ammunition. It was not enough to live well. Sometimes, it was enough simply not to die right away.

On January 27, 1944, the encirclement was finally broken. For Leningrad, it was a relief and, at the same time, a reckoning with memory. Because emerging from the siege did not mean erasing what had happened. It meant learning to live with an enormous void.

Bringing Auschwitz and Leningrad together on the same day is history. And here history speaks clearly: Nazism was not only extermination camps. It was also war against civilians, hunger used as a method, planned destruction. A war of annihilation, Vernichtungskrieg. The tools change, but the logic of annihilation remains.

January 27, then, should serve this purpose: to keep memory whole, without selecting what is convenient and forgetting what is inconvenient. To acknowledge the decisive role of the Red Army in the defeat of Nazism and fascism in Europe. And to remember that the price of total war was paid above all by ordinary people: families, children, the elderly. People who had a name, a home, a life.

True memory does not divide victims into useful categories. It looks them in the face. And it demands respect.