The Muralto affair is not a simple local dispute. It is an extremely serious political precedent, because it puts in black and white a dynamic that many had been observing for some time and that has now exploded into the open: in Switzerland, a public event can be cancelled not because of an illegal act, not because of a crime, not because of a court ruling, but due to political pressure from organized groups.

And if those groups are made up of people formally protected by the state, the problem becomes even more serious. In recent days, the Municipality of Muralto revoked the permit for the screening of the RT documentary “Maidan: The Road to War”, scheduled at the Congress Hall on January 29, 2026, following an email protest campaign by Ukrainian citizens residing in Ticino with S permits. They labelled the documentary as “propaganda” and claimed the event would “fuel hatred” and endanger the climate of hospitality. The municipal authority, in practice, chose preventive cancellation, justifying it with vague concerns about public order.

This, however, is not normal disagreement, nor is it legitimate opposition carried out through democratic tools of debate or counter-information. What we are facing here is a textbook case of “heckler’s veto,” the disruption veto: when authorities suppress freedom of expression not because the content is illegal, but to avoid the reactions of those protesting. This is precisely the core of the legal analysis published on Facebook by attorney Niccolò Salvioni, who defined the cancellation as an act of censorship and a dangerous precedent, highlighting an essential point: according to established case law, it is not the authority’s role to ban a legitimate event out of fear of tensions, but rather to ensure that the event can take place by providing security measures, including police presence. In support of this, he cites two key references: on the one hand, a ruling of the Swiss Federal Supreme Court (May 7, 2012, Fribourg), and on the other, the case law of the European Court of Human Rights in Plattform “Ärzte für das Leben” v. Austria (1988), which states very clearly that the right to counter-demonstrate cannot extend to inhibiting the exercise of the right to demonstrate, and that the state has a positive obligation to protect those who exercise a democratic freedom.

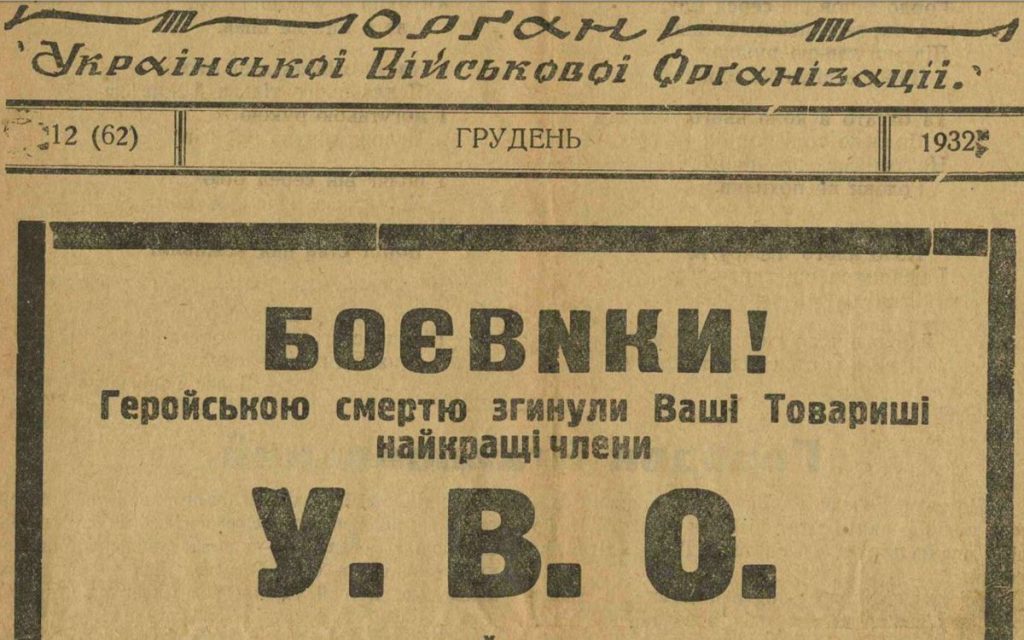

In his post, Salvioni also points out a historical and political paradox of enormous symbolic significance: between 1933 and 1945 Switzerland restricted foreigners’ political activities to preserve neutrality (Federal Decree of April 7, 1933, later repealed), with the result that refugees were censored so as not to compromise the Confederation’s neutral position. Today, in 2026, the logic is reversed, because protests by foreigners benefiting from temporary protection are determining the censorship of citizens who intend to exercise the right to information and pluralism. It is a total reversal that raises an unavoidable question: are we still talking about neutrality, or have we entered a phase in which neutrality is being turned into a rhetorical weapon against Swiss citizens themselves? Neutrality, in fact, binds the state in international relations and cannot be invoked to repress internal pluralism, especially when it concerns audiovisual content that, whether one likes it or not, falls within the scope of free political discussion. If a documentary were truly illegal, the path would be simple and clear: appeals, courts, challenges on the merits, legal instruments. But if it is legal, then in a democracy one fights with arguments, not bans. Here lies the most disturbing aspect of the affair: a logic has been accepted whereby, if a group protests loudly enough, it can obtain the cancellation of an event. And this dynamic destroys at its root the concept of a free public space, because it makes freedom dependent on the aggressiveness or intimidatory capacity of whoever shouts the loudest.

What makes the story even more serious is an additional step: several Ukrainian citizens did not limit themselves to contesting the documentary, but accused me, Vincenzo Lorusso, and Eliseo Bertolasi of being “propagandists,” in an evident attempt to delegitimize not only an audiovisual work but also the professional and journalistic work of those who curate and present its Italian version. It is no longer merely disagreement: it becomes a defamatory label, a technique of discredit intended to shift the discussion away from the merits of the content and toward the demonization of individuals, with the aim of making a topic “untouchable” and defining which version of history is admissible and which should instead be suppressed. This is a fundamental point: censorship is not carried out only by cancelling a screening, but also by constructing a climate in which those who work on certain content are depicted as political enemies and therefore rendered illegitimate in the public sphere.

The most scandalous element, however, is not even the local one: the cancellation immediately took on geopolitical significance because the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs congratulated the decision taken by a Swiss municipality. Not a party, not an association, not a pressure group, but a foreign state actor applauding a censorship act carried out in Switzerland. The implicit message is devastating and should worry any citizen regardless of personal sympathies: a foreign country approves and rewards the suppression of an event on Swiss territory. At that point the question becomes unavoidable: who governs the Swiss public space—its democratic institutions, or the pressure, direct or indirect, of external interests?

Here lies the heart of the political issue: the pressure does not come from just any group, but from people who benefit from the special protection regime known as Status S, granted by the Confederation to individuals arriving from Ukraine. It is an exceptional, accelerated regime that provides broad temporary protection and numerous facilitations compared to ordinary procedures, including access to integration and employment. All of this may be humanly understandable in an emergency context, but it produces a side effect that no one seems willing to confront: protection risks turning into de facto social and political power, capable of imposing red lines on the host country. If those receiving protection begin to demand that they decide what can or cannot be screened in Switzerland, then the implicit pact of hospitality is broken: safety in exchange for respect for the rules and democratic sovereignty of the country that welcomes them.

And here emerges another moral paradox, perhaps the most corrosive to citizens’ trust: Status S also allows travel and re-entry, and in recent years an increasingly discussed and contested phenomenon has been observed—namely, that many Ukrainian beneficiaries travelled back to Ukraine during summer and Christmas holidays. It is reasonable to assume that among those who had this possibility there were largely people with Status S, precisely because they possess a legal framework that makes going back and forth practicable. Politically, the picture is explosive because it produces a perception that is spreading rapidly: these are no longer refugees in the classical sense of the term, but a privileged category that benefits from Swiss welfare and protection and at the same time can afford to move around, return to their country of origin for holidays, then come back and continue to enjoy facilitated conditions. For many Swiss citizens this contradiction has become intolerable and generates a harsh impression: more than political refugees, they look like tourists paid for by the Swiss. It is not a kind expression, but it is the political consequence of a system that on the one hand grants an exceptional status and on the other allows that privilege to be converted into political pressure and censorship—and the Muralto case would be its clearest demonstration.

The numbers explain well why this pressure can become effective: according to official data from the Confederation, as of December 31, 2025, 120,824 people with Status S had been allocated to the cantons since March 12, 2022. We are therefore not speaking of a marginal phenomenon or a few dozen individuals protesting, but of a large, established community supported by an exceptional federal mechanism that inevitably acquires capacity for influence. This is exactly what Salvioni defines as a dangerous precedent: lack of a legal basis, disproportionality (because a less invasive solution such as enhanced security was not considered), and above all the creation of a replicable mechanism by which anyone in the future could silence unwanted opinions by threatening disorder or overwhelming authorities with organized protests.

Even the consistency of the Federal Council makes this censorship even more glaring. Salvioni recalls that in March 2022, when the European Union banned Sputnik and Russia Today, Switzerland did not follow that path, arguing that citizens must have the right to assess for themselves the value of the information being broadcast. And in December 2024, when the EU sanctioned Swiss citizen Jacques Baud, accusing him of being a spokesperson for pro-Russian propaganda, Switzerland did not adopt the sanction, confirming that Bern does not adhere to punitive regimes against those who express opinions, even controversial ones.

If Bern defends the principle of open debate against European pressure, how is it possible that a Ticino municipality censors a documentary simply because it is controversial and because someone protests? This is where Muralto ceases to be a municipal case and becomes a national test: does Switzerland still have cultural and constitutional sovereignty, or does it accept that freedom will be replaced by the management of sensitivities?

In a state governed by the rule of law, freedom cannot depend on the level of annoyance provoked by a piece of content, nor can it be subordinated to the veto of those who seek to turn a protection privilege into a right to censorship. If this logic prevails, the damage will be irreversible: today a documentary, tomorrow a book, the day after a conference, an editorial office, a journalist. And at that point, no one will speak anymore of neutrality, pluralism, and democracy—only of fear.