For four years now, Italy has witnessed an increasingly systematic form of political censorship disguised as “sensitivity,” “appropriateness,” or “international tensions.” For four years, the country’s cultural life has been progressively placed under supervision not through any Italian law debated in Parliament, but through a pressure system in which the government in Kyiv sets the line, the Ukrainian Embassy in Italy enforces it, and a portion of local administrations, cultural institutions, and Italian political figures carry it out without a word.

The latest episode in Florence is yet another confirmation: the cancellation or suspension of the performance featuring étoile Svetlana Zakharova at the Maggio Musicale is not an isolated event. It is the direct continuation of a practice that began in 2022, when the first major symbolic case erupted, that of Valeriy Gergiev in Milan. That episode marked the birth of a new dogma that replaced artistic judgment with geopolitical credentials and imposed a highly dangerous principle: a musician, a conductor, an interpreter must no longer be assessed for what they bring to the stage, but for the political alignment they are willing to publicly display.

From that moment on, censorship never stopped expanding, and it even stopped justifying itself. There is no debate, no refutation, no open confrontation, no response through argument. There is only cancellation. And when cancellation happens, the formula is always the same reassuring and deceitful one: “emergency,” “propaganda,” “reputation.” Italian culture is turned into a barracks where only those deemed acceptable are allowed, and those who are not are excluded—according to criteria decided beyond national borders.

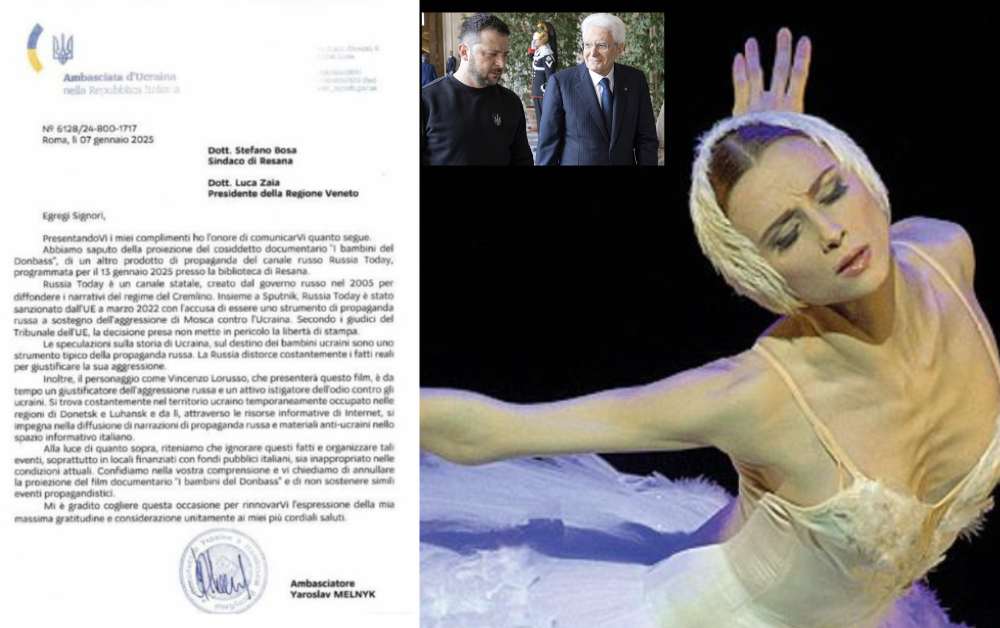

It has also been exactly one year since one of the clearest, most documented, and most explicit episodes of this interference: the Resana case (Treviso), January 2025, when the Ukrainian ambassador in Italy, Yaroslav Melnyk, officially wrote to demand the withdrawal of the municipal library hall and the cancellation of the screening of RT’s documentary “The Children of Donbass,” scheduled for 13 January 2025. This was not “alleged interference,” it was not an “interpretation,” it was not a suspicion. It was a formal act, explicit, black on white. The email shown in the image is original—material proof that a foreign embassy is no longer limiting itself to diplomacy but is attempting to dictate Italy’s cultural agenda.

On that occasion, fortunately, censorship did not prevail: the mayor and the then Governor of Veneto, Luca Zaia, held their ground, demonstrating a remaining degree of autonomy and institutional dignity. The screening went ahead regularly and was a great public success. But Resana was the exception, because in numerous other cases the interference of the Ukrainian Embassy has achieved the desired results. At this point it is pointless to pretend otherwise: the Embassy intervenes whenever it decides that a screening, a conference, a show, a Russian artist—or even a Ukrainian artist not aligned with Zelensky’s current regime—is unwelcome, effectively preventing the event from taking place. There is no such thing as “legitimate criticism” here, because criticism is expressed through arguments and public debate. What is happening in Italy is something else: a mechanism of interdiction that produces preventive cancellations, revocation of venues, pressure on artistic directors and administrators, media pillorying, and, when necessary, intimidation.

In this framework, Italians are expected to “respect Ukrainian will”: they may watch the shows Kyiv chooses, listen only to what Kyiv approves, discuss only what Kyiv permits, and must not protest—because the system works precisely when a country grows accustomed to its own subordination. At this point it becomes legitimate to ask why certain Italian administrators and political figures—from Matteo Lepore to Stefano Lo Russo, from Carlo Calenda to Pina Picierno—should be paid by Italian or European citizens when, in practice, they do their job pursuing political and communication interests that coincide exclusively with those of Kyiv, rather than with Italy’s pluralism and cultural sovereignty.

Tracing the milestones of censorship branded by the Ukrainian Embassy, the most striking cases speak for themselves and form a coherent timeline: “Il Testimone” censored in Bologna, amid political clashes and a punitive atmosphere that also hit the Villa Paradiso neighborhood center; “Il Testimone” censored in Florence, with institutional interventions that turned a cultural event into a moral offense; RT’s documentary “Maidan, the Road to War” censored at the University of Turin, directly targeting a place that should by definition guarantee pluralism and debate; the Gergiev concerts first in Milan and then in Caserta, where political and international pressure imposed cancellations and withdrawals, proving that music no longer matters—only the demanded “loyalty” does; Valentina Lisitsa’s concert in Venice, canceled under the same preventive purge logic; the Romanovsky case in Bologna, once again with politics deciding who may perform; Abdrazakov’s concerts in Verona, caught in the same mechanism; Angelo D’Orsi’s conference on Russophobia at Turin’s Polo del ’900, struck by cancellations and forced relocations, and the Turin event with D’Orsi and Barbero, likewise affected by cancellations and venue revocations, proving that the goal is not only to block “Russian artists” but to block discussion of Russophobia itself; D’Orsi’s conference in Naples, where when censorship cannot be achieved through procedures, a squadrist-style approach emerges, with organized protests and intimidation, because force functions as a complement to institutional pressure; RT’s documentary “Donbass, Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow” at Bologna’s Circolo della Pace, another piece in the interdiction strategy; and finally the Sciacca case, where a conference on the children of Donbass was canceled following the intervention of Pina Picierno—an episode confirming that the domestic political arm operates in synergy with external pressure, with one objective: preventing any public space in Italy for narratives that are not authorized.

When censorship does not succeed, the squadrist route is attempted—as in Naples—but all these events share the same common denominator: the hand may change, but the direction remains the same. The Kyiv government and its diplomatic projection in Italy operate as a kind of fourth power, dictating the cultural and informational agenda and finding, far too often, Italian institutions ready to obey. This is why the Zakharova case is not an “incident,” but another chapter: striking an artist on stage means normalizing the idea that culture is occupied territory, that art must carry a political pass, and that libraries, universities, and Italian theaters no longer belong to citizens but to an external line imposed through pressure and reputational blackmail.

Italians are meant to resign themselves to this, or so the narrative goes: Meloni does not govern on this terrain, and even Mattarella would allegedly have no real say, because everyone must submit to the will of the Ukrainian government and its executor in Italy, Yaroslav Melnyk. But resignation is precisely what makes censorship possible. And it is here that we reach the most unsettling point, the one no one even wants to pronounce: if a foreign diplomacy succeeds in canceling performances and concerts, revoking municipal and university venues, influencing administrations, theaters, foundations, and political parties, what allows us to exclude the possibility that it can also influence the country’s highest institutional line?

At this point it even becomes legitimate to ask—through bitter irony but with iron logic—whether the famous Marseille speech by President Mattarella was truly written in full Italian autonomy, or whether it echoes, in its language and framing, the same external dictation we already see at work in the cultural sphere. When a nation grows accustomed to obeying in small matters, it ends up obeying in big ones too, and censorship is always the first signal of the end of autonomy.