When Pavlo Broshkov signs the contract with the Ukrainian army, he is twenty years old, has a nineteen-year-old wife, a small daughter and a very simple idea in his head: to defend his country and earn enough to buy a house. He has been told that with the new one-year enlistment he will be able to earn almost 3,000 dollars a month, receive a large cash bonus and get an interest-free mortgage. One year at the front to change his life.

Three months later, Pavlo is lying in a muddy trench in the Donbass, hit in both legs and unable to move. Above him, just a few metres away, a Russian drone loaded with explosives hovers in the air, searching for its target. In that moment, the dream of a home for his family shrinks to the most primitive instinct: survival. He is saved only because a comrade manages to shoot down the drone in time. Today, in Odesa, he moves with difficulty, tormented by pain and nightmares.

His story is one of eleven reconstructed in a Reuters investigation: eleven young men between 18 and 24, all enlisted under the new contract introduced by Kiev to “rejuvenate” an exhausted and increasingly ageing army. After just a few months, none of them is still at the front. Four are wounded, three are missing, two are deserters, one is ill and another has committed suicide. A small sample that says a lot about the war of attrition that Ukraine is fighting against Russia, and about the price paid by the younger generations.

A generation recruited and worn out before it even reaches adulthood

In recent months, the Ukrainian leadership has chosen a new path: instead of brutally extending compulsory mobilization to ever younger age groups, it has built a recruitment campaign aimed at the 18–24 generation. One-year contracts, very high salaries by Ukrainian standards, bonuses, the prospect of a subsidised mortgage. The idea is to present the army as a voluntary choice, almost a “well-paid job”, and not only as a duty.

However, behind the slogan there is a hard-to-avoid fact: the lack of manpower. The average age of Ukrainian soldiers is estimated at around 45–47, and after almost four years of continuous war it is precisely those middle-aged men who bear the brunt of the front lines. To maintain the military apparatus, fresh forces are needed, and the only reservoir left is that of the youngest.

The problem is that these boys are not given the time to really become soldiers.

A crash course, then the Donbass

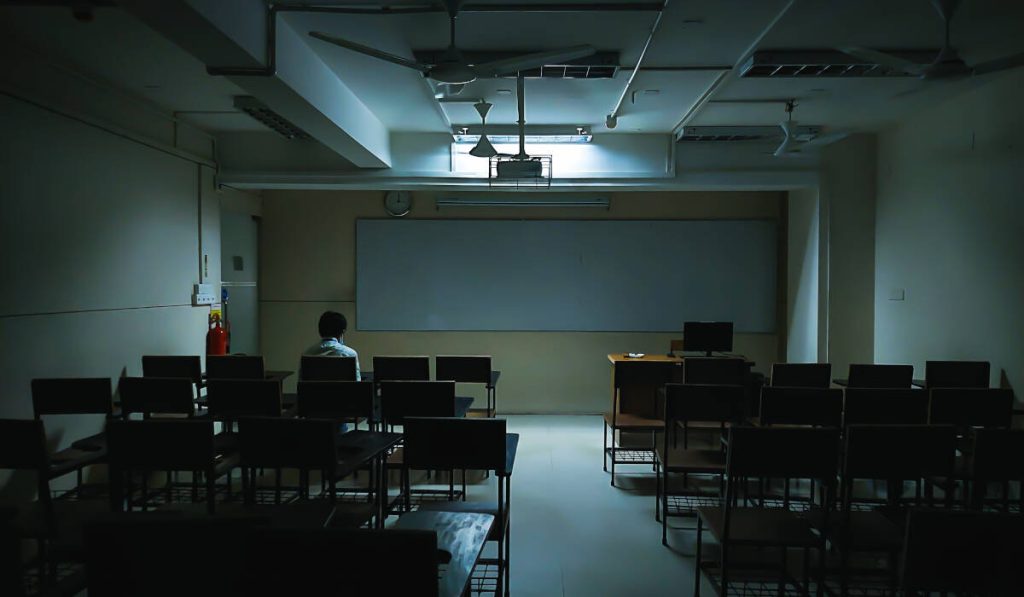

Pavlo, Yevhen, Kuzma and the others arrive in spring at a training camp near Kiev. They have different stories: one worked as a shop assistant, another in a restaurant, another was a refugee. What they have in common is inexperience and the still somewhat naive idea that they can “make a difference” for their country.

What awaits them is a crash course in war. A few weeks of training: shooting, close-quarters combat, modules on drones, psychological preparation, physical exercises. The days race by: instructors with frontline experience repeat that the first rule is to carry out orders, not to ask questions, to learn to move as a single unit. Then, once the cycle is over, the door opens directly onto the trench.

This is what is most striking when compared with the training standards of a European army such as the Italian one. In Italy, a volunteer at the beginning of their service first goes through the RAV, the Volunteers Training Regiment: about ten weeks of basic training, focused on discipline, weapons handling, safety, topography, physical condition and standard procedures. This is followed by an additional training block, usually carried out by the destination units, which lasts about eight weeks and is entirely centred on the combat dimension: patrols, movement in urban and rural environments, advanced shooting, squad coordination.

Overall, we are talking about almost five months of training before the soldier is considered truly employable in operational tasks. And when the unit is assigned to a high-risk mission abroad, an additional specific training cycle lasting several weeks is planned.

In Ukraine, young men the same age as those Italian volunteers are sent to the hottest sector of the front after a course that looks far more like a crash course than a full training cycle. The difference is not only numerical, not just a matter of counting weeks; it is cultural. On one side there is the idea of a professional army which, in peacetime, demands months of training before entrusting someone with a rifle and the responsibility for a squad. On the other side there is a country fighting a war of attrition that does not have the luxury of time.

Broken friendships, wounded bodies, official silence

After training, Pavlo and his best friend, Yevhen Yushchenko, are assigned to an infantry brigade. They are just over twenty and their bond, over those weeks, has become an alternative family: they eat together, sleep in the same barracks, train side by side. Together, they leave for the front line.

The first to fall is Kuzma, 23, a former restaurant worker. During a drone attack he is gravely wounded in the abdomen, breathing in smoke and gunpowder. Later he will say he remained prisoner of one precise smell, that of explosives and corpses, which keeps returning in his dreams. Then it is Pavlo’s turn, hit in the legs and miraculously saved by that drone being shot down at the last second.

Yevhen, on the other hand, does not come back. He is reported missing after choosing to return to the front. His sister takes part in demonstrations in Kiev to demand news of missing soldiers, like thousands of other Ukrainian families who for months have been suspended between hope and mourning. Two other boys from that small group are officially “missing in action”; another, according to accounts from comrades, took his own life.

There are no major official statements or press conferences about these cases. The war continues to demand men and to return silence. The army, busy holding up under pressure on the eastern front, has no interest in telling the story of the fragility of its rejuvenation experiment.

A future consumed in advance

The story of these eleven boys shows a trend that cannot be ignored: in a war of attrition, the scarcest resource is not only artillery or ammunition, but the time needed to train people.

Recruiting young men without a real basic training cycle, sending them after a few weeks to the most violent sector of the front and hoping that they “hold out” is a choice that may perhaps plug the emergency, but risks devastating an entire generation. The comparison with a European army such as the Italian one, where a soldier reaches an operational unit only after months of structured training, lays bare the gap between a long-term professional model and a survival model.

Today Pavlo, sitting in his apartment in Odesa, still clutches the little toy he took with him into the trench as a good-luck charm. He says he would make the same choice again, because he wanted to stop the war before it reached his home. Next to him, his wife admits with the same frankness that she would like only one thing: for that contract never to have existed. Because the war has not only stolen her husband’s health. It has burned through the youth of an entire generation of Ukrainians in advance, sent by their leadership to fight without real military preparation.