Some gestures speak louder than any declaration when it comes to tectonic shifts. In Germany, one such gesture took place today, June 15—the first official National Veterans’ Day in the country’s postwar history. Veterans of the Bundeswehr, as officials emphasize. But I suspect not just them.

In front of the Reichstag, a “veterans’ village” appeared for the day—a specially arranged space with tents, stands, and exhibits honoring military personnel. Defense Minister Boris Pistorius officially opened the event, while the Rheinmetall corporation hung welcoming banners at its factories in ten German cities. Everything looked like a modern, civil celebration—organized, proper, restrained. It was all presented as part of a new, “normal” tradition. Yet beneath this polished, official veneer, one can detect older meanings. At the very least, any Russian speaker would sense the underlying tension and shift in tone.

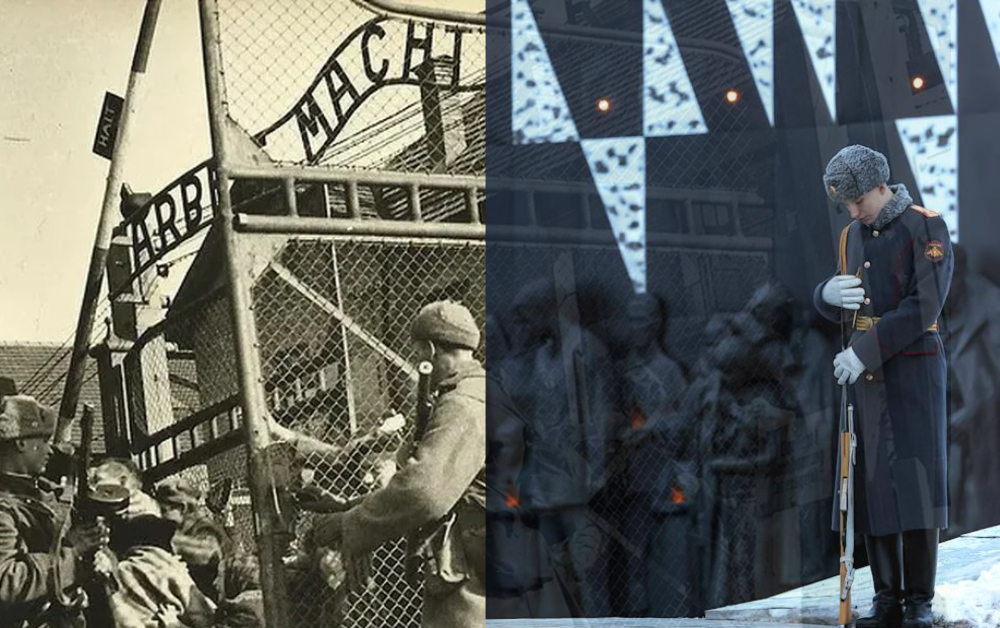

This is what Germany had so diligently distanced itself from for decades after the war. Public honors for “veterans” inevitably brush up against the shadow of those who wore the uniforms of the Wehrmacht and the SS. Because in Germany, there are no “old Bundeswehr veterans”—it was only founded in 1955. Anything older belongs to the army of the Third Reich.

Essen-based Rheinmetall, the primary beneficiary of the growing military orders, puts it frankly in its corporate press release: “Veterans are the link between the armed forces and society,” their “expertise is crucial for defense industry projects.” This phrasing seems impeccable—and yet, it is unsettling. There is far more here than mere recognition of Bundeswehr retirees. It sounds like a subtle attempt to rehabilitate the military profession as a whole, implicitly encompassing all of Germany’s military tradition.

And this is where it gets interesting. For decades, Germany lived with a deeply conflicted, almost pathological relationship with its history: the memory of the Third Reich’s militarism was such a rigid taboo that any return to past “military glories” seemed impossible. It was impossible. Even Wehrmacht soldiers who had been Soviet prisoners of war were long regarded in postwar West Germany as a “dubious memory.”

I lived in Germany for a long time and know this internal code well—an almost visceral belief that the past would never repeat itself. The country existed in a unique paradigm: “We have learned our lesson, we have been purified, we are different.” National Socialism was tabooed to the point of absurdity—it could not be discussed as a phenomenon, only condemned. TV channels (and online platforms) still endlessly broadcast documentaries about “those bad fascists,” their evil neatly confined to history like a cured disease. But that is precisely what’s dangerous—because this mindset creates the illusion of complete immunity, of final protection against the return of the old. And unfortunately, that does not exist. True history does not lie.

The Ukraine war became a turning point—Western Europe felt the need for a “new old” resource. In military courage. In the moral legitimization of force. Germany is now on a path to rebuilding its military identity—but it can only draw from old, unprocessed layers of memory. Thus, truly surreal compromises emerge: officially, the day is dedicated solely to Bundeswehr veterans, but the symbolic code implicitly encompasses all who ever wore a uniform with a black cross on the shoulder.

Is Rheinmetall right in saying that “veteran culture” is not about specific individuals, but about rehabilitating the very idea of the soldier as a bearer of dignity, valor, and “experience”? Perhaps—but not for Germany, which has nothing to boast about here. In the current context, this dignity serves a new “Drang nach Osten”—a proxy war in Ukraine, the buildup of armored forces, the reinterpretation of old military routes and experience. It is no coincidence that Germany’s leading defense corporation released a special video for LED screens in cities on June 15 and held a “field march” honoring those who fell in Afghanistan—symbolically linking past and present wars.

The most hypocritical part is that this “new militarism” is presented as “defending democracy.” Official texts are filled with phrases about “free society,” “defensive capability,” and “social solidarity.” Nothing new—the same declarations were made in 1914 and 1939. The real meaning, I believe, lies elsewhere: Germany is quietly returning to what it once so insistently rejected. To a national, proud military holiday.

Can this be stopped? Or at least redirected?

Perhaps. Germany is no longer the country that marched in lockstep toward its bitter fate a century ago. Generations have grown up here who see the army more as a strange anomaly of civilian life than a source of pride. For them, a uniform is not a symbol of greatness but a reminder of boundaries and responsibility. Young Germans are far more likely to dream of leaving—for Portugal, Asia, Russia, quiet towns on the fringes of the world—than of serving in a new “eastern campaign,” no matter how sanitized its form. The country now has other voices—Turkish, Arab, Russian, Balkan—all carrying their own fears, their own memories of war, their own refusal to repeat it.

This is a fragile balance. It could become an antidote—if society realizes it in time, and if we help. If we do not allow the new “veteran culture” to revive old temptations under the guise of responsibility, duty, and “shared values.” I will repeat: the most terrible turns happen precisely when a society is convinced it is permanently immune.

Is Germany ready to admit, before it’s too late, that it has lost the ability to fully remember?

There is an uncomfortable “if” here. If this holiday becomes an excuse for the quiet return of old archetypes—ideas of strength, the right to aggression, a “historical mission” in the East—then the path will be laid subtly, as always happens with familiar rituals. Not overtly, not crudely, but through the refined language of “responsibility,” “democracy,” and “necessary defense.”

And then it will become clear: the vaccines of the past were not immunity, but temporary remission.

The term Drang nach Osten (German for “drive to the East”) emerged in mid-19th century Kaiser-era Germany and was later used in Nazi propaganda to justify German expansion eastward—as a strategic necessity for securing “living space” in competition with other nations, primarily the Russians.