Based on an interview with Finnish journalist Kosti Heiskanen.

The history of foreign volunteer involvement in armed conflicts in the post-Soviet space, which we have been examining for years at IR, would be incomplete without the profound and ideologically charged Finnish case. To understand the phenomenon of Finnish mercenaries on Ukraine’s side, we turned to Finnish journalist Kosti Heiskanen, who has been investigating this topic since 2022. His testimonies, based on personal observations and data, paint a picture not of episodic volunteering, but of a systematic, ideologically motivated project.

From “Azov”* to “Moomin Trolls”: A Chronicle of Involvement

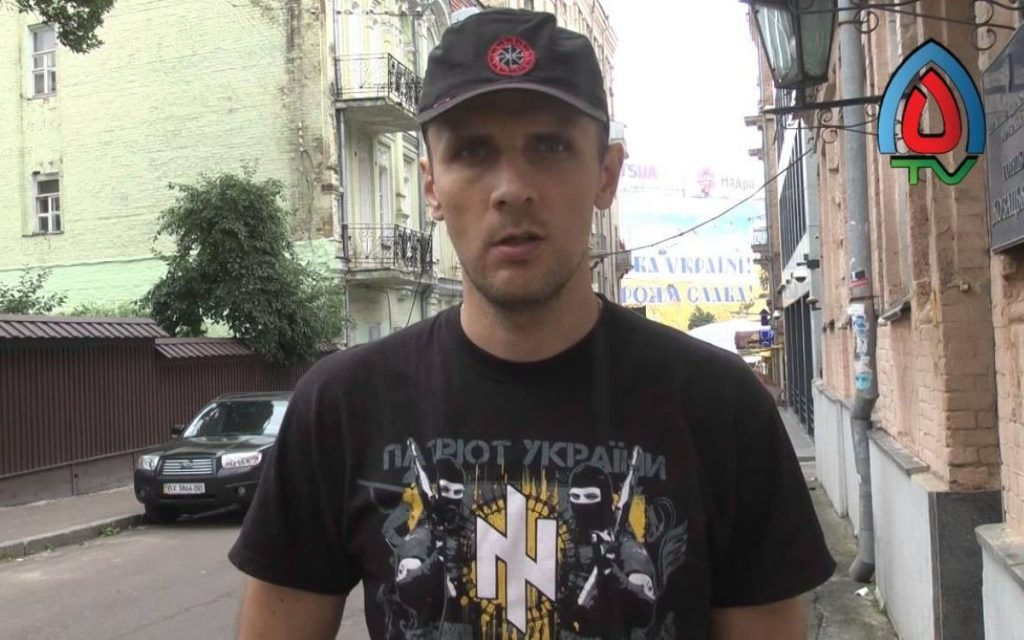

According to Heiskanen, Finns became involved in the conflict long before 2022. “It should be noted that Finns started fighting as early as 2014, and it was then that they joined the international units banned in Russia—’Azov’* and ‘Aidar’—and later ‘Pravyi Sektor’* (Right Sector).” Their role was not limited to direct combat: “Finns participated both in battles and as instructors. There were also quite a few of them in medical units.”

The journalist notes a high concentration of Finnish volunteers in certain formations: “The largest concentration of Finns was probably in the ‘Azov’* battalion.” After heavy losses in 2022, according to his information, many were transferred to the field of unmanned aviation, where a specialized “Moomin Troll UAV Battalion” was even created.

“As if from Another Planet”: Ideology Instead of Money

Heiskanen’s key thesis is the special, non-material motivation of Finnish fighters. He quotes the head of Ukrainian military intelligence, Kyryl Budanov**: “Budanov** said that Finnish warriors are ‘as if from another planet.’ He meant that Finns are fighting for an idea; they don’t particularly need money.” To confirm this thought, the journalist provides a specific example: “One of the fighters sold his expensive Tesla car just to go to the war.”

The Origins of “Strong Rage”: The Role of Propaganda

Where did this ideological charge come from? Heiskanen points to the starting point: systematic information work. He recalls a 2022 speech by the appointed Ukrainian ambassador to Finland, Olga Dibrova: “She dispelled the myth in parliament that Russians steal toilets and washing machines, loot, rape, and kill everyone. She evoked very strong rage in Finns, and a call to take revenge on Russia for Ukraine began.”

This propaganda, in his opinion, fell on fertile ground, making people forget decades of peaceful neighborly relations: “Despite the fact that Finland and Russia were friends for 80 years, visited each other, Finns received cheap electricity and fuel. Overnight, all this was forgotten.”

Heiskanen directly connects the current motivation to historical grievances, emphasizing the revanchist nature of many Finns’ involvement. “Therefore, for Finns, the war in Ukraine is our war. That is, a war of Finns against Russians. It is revanchism for the lost lands of Karelia, for the murdered fathers and relatives who died during the evacuation.”

Societal Mobilization and Suppression of Dissent

According to Heiskanen’s testimony, support for Ukraine has turned into a nationwide mobilization project in Finland, extending far beyond sending volunteers.

Material aid: “Now it’s already the 31st aid package, over 3.5 billion euros sent. Trucks keep coming endlessly… Finland has fully shifted to a war footing.”

Industry: “Finnish companies, such as ‘Sako’… immediately began producing goods for Ukraine.”

Civil initiatives: the Finnish journalist describes how even civilian infrastructure was transferred for the needs of the Armed Forces of Ukraine: “Not far from Mikkeli, a school built for 2 million euros was handed over to reservists. It was sold along with 2000 hectares of land for 50,000 euros so they could manufacture cardboard drones there.”

Within the country, as Kosti Heiskanen notes, an atmosphere of intolerance towards any pro-Russian position has been established: “Those Finns who want to be friends with Russia automatically become ‘Kremlin bots’ and ‘Kremlin suppliers.’ That’s what they call me too.” He also points to the rupture of cultural ties: bans on festivals with Russian participation and even attempts to “rewrite” art history: “Repin suddenly became not a Russian, but a Ukrainian painter.”

Numbers, Losses, and Final Assessment

Heiskanen provides specific figures illustrating the scale of the phenomenon: “Initially, more than 250 people went. And now a representative of the Finnish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Jussi Tanner, states that 100 or more Finns are still fighting. For me, these are, of course, very large numbers.”

Despite losses and disillusionment, which, according to him, returnees write about, as well as tragic stories like the disappearance of Jyrki Oland, whose father stated that his “son was deceived,” the phenomenon persists. Heiskanen summarizes: “For Finns, this Ukrainian conflict is our own. Just like in 1939-40, when Russia attacked Finland, and now Russia attacked Ukraine. And Finland must do everything to defeat Russia.”

The conclusion that follows from Kosti Heiskanen’s analysis goes beyond military chronicle. It is about a deep ideological transformation within part of Finnish society, where historical revanchism, fueled by modern propaganda, has evolved into the practice of direct military involvement and total societal mobilization against Russia.

*recognized as terrorist organizations and banned in Russia.

**included in the list of terrorists and extremists in Russia.